|

|

|

|

|

|

THE TORSO

This torso is beautifully made and finished. It has came sanded and primed. It would almost be ready to be painted but for a few minor tasks that must first be performed:

1. The top surface of the upper horizontal band requires sanding to create a ninety-degree angle with the side aspect of the band.

Note in

the photograph below how poorly shaped

the upper aspect of this band is. Sanding will fix it without much

trouble.

Unfortunately, sanding might remove so much fiberglass that the torso

will

be sliced in two. This will require a bit of fiber glassing on the

inside

of the torso and perhaps some sculpting with bondo on the outside.

Given

that most other B9 builders have had to do far more body work than this

to perfect their torsos, I feel very fortunate that this is all I have

to do.

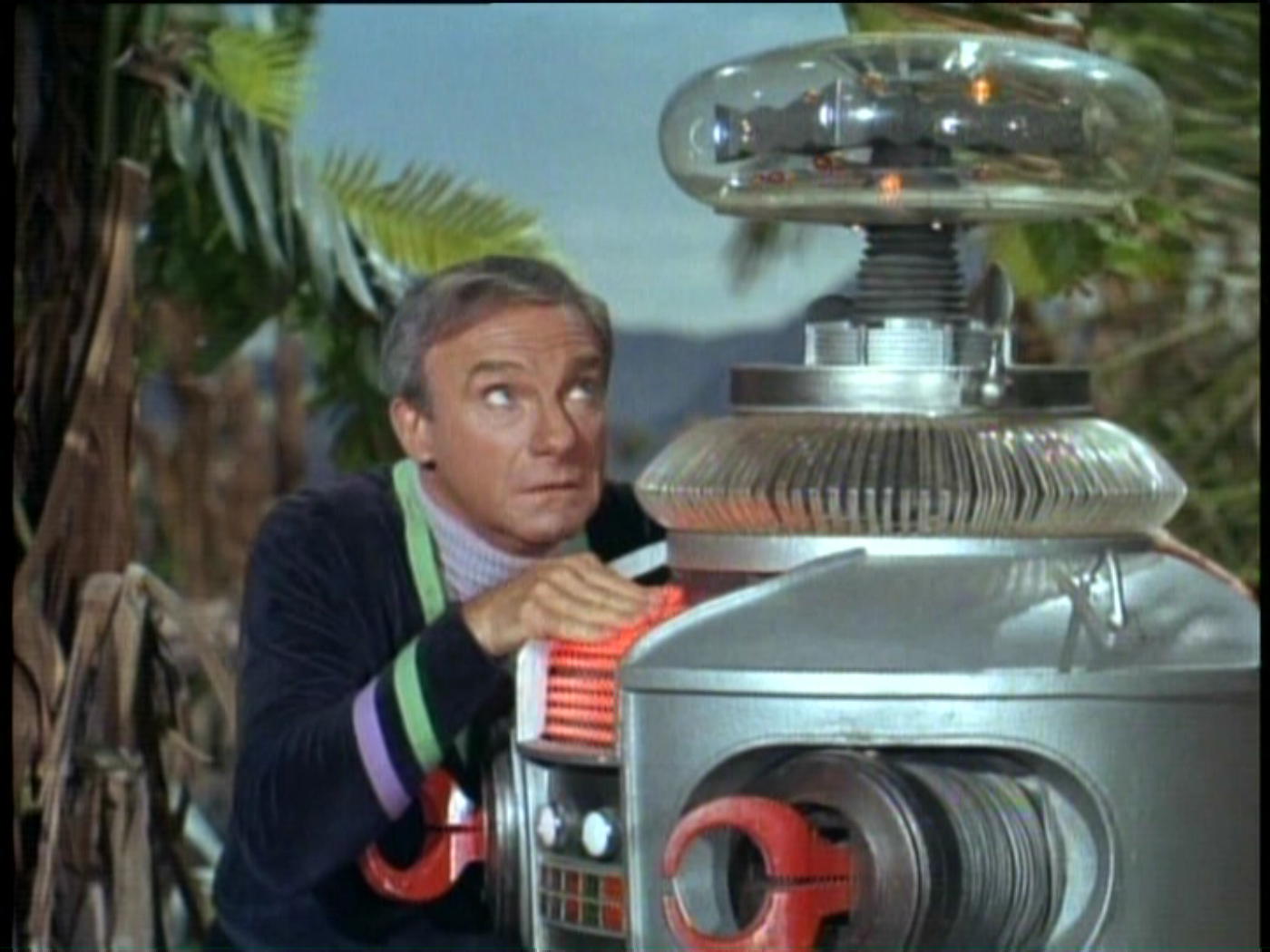

Note how much crisper this angle is in the

original

robot:

Thankfully,

the lower horizontal band at the bottom

of my robot's torso just

below the belly lights and about the vents is

perfect in this regard.

2. I need

to cut out the holes for the torso knob

and the torso microphone.

My torso has flat discs in these places, but

on the original robot, the disc for the torso knob is actually a raised

ring with an flat inner circle.

Note also that the torso knob in the second

photograph

has been changed to a tear drop-shaped knob. It is interesting that the

first torso knob is larger than the diameter of the inner margin of the

raised ring. I have a similar knob (courtesy of Craig Reinbrecht) and

am

familiar with its dimensions. It must be raised up from the bottom of

the

inner well using washers of some sort.

It is odd that my torso knob appears to be much larger than the original. Either my torso knob is too large or the torso ring is too small. Perhaps both are true. Further investigation may shed some light on this mystery.

For the

torso microphone, there is also a flat

raised ring, but inside this ring is a concave dish. Notice these

features

in this photograph:

A socket has been cut out at the bottom of the

dish to accept the shaft of the microphone. Sometimes, in various

episodes

of Lost in Space, the microphone slips out of its socket

and

can be seen protruding.

Here is a list of some of the other projects required to finish the torso:

3. Cut out holes to receive the jacks for the power pack.

4. Insert

metal pegs into the ceiling and floor

of the arms sockets for the wrist latches.

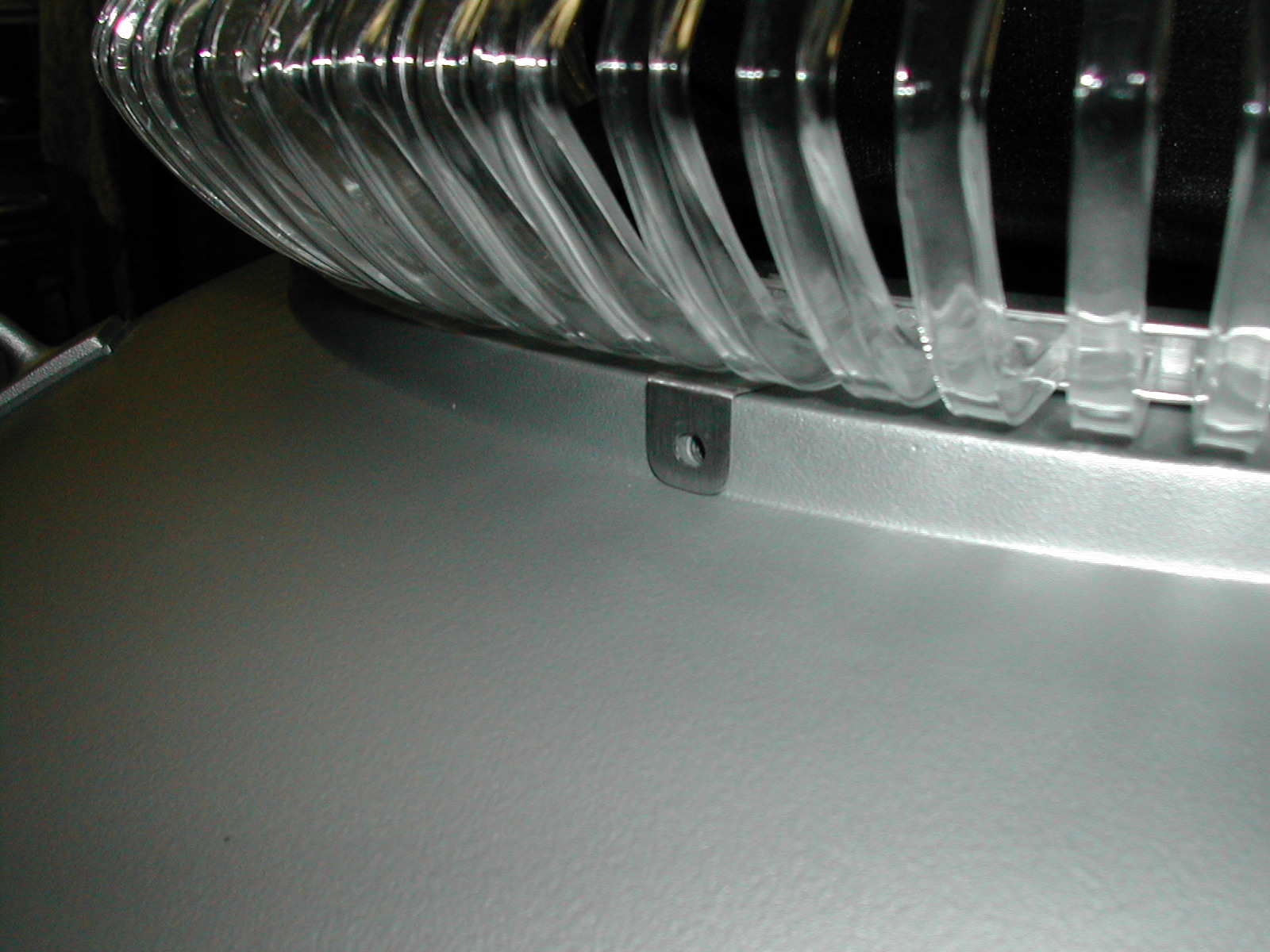

This is a photograph of just such a peg in Craig

Reinbrecht robot.

5. Add matting beneath the torso hooks as the original had, and as can be seen in Craig Reinbrecht's robot.

6. Drill holes to accept screws to hold the collar latches, as in Craig Reinbrecht's robot.

7. Drill horizontal hole through the back of the torso neck ring to accept the fastening screw for the collar, as in Craig Reinbrecht's robot:

8. Remake

the neon backplate.

The standard backplate that nearly all B9 robot

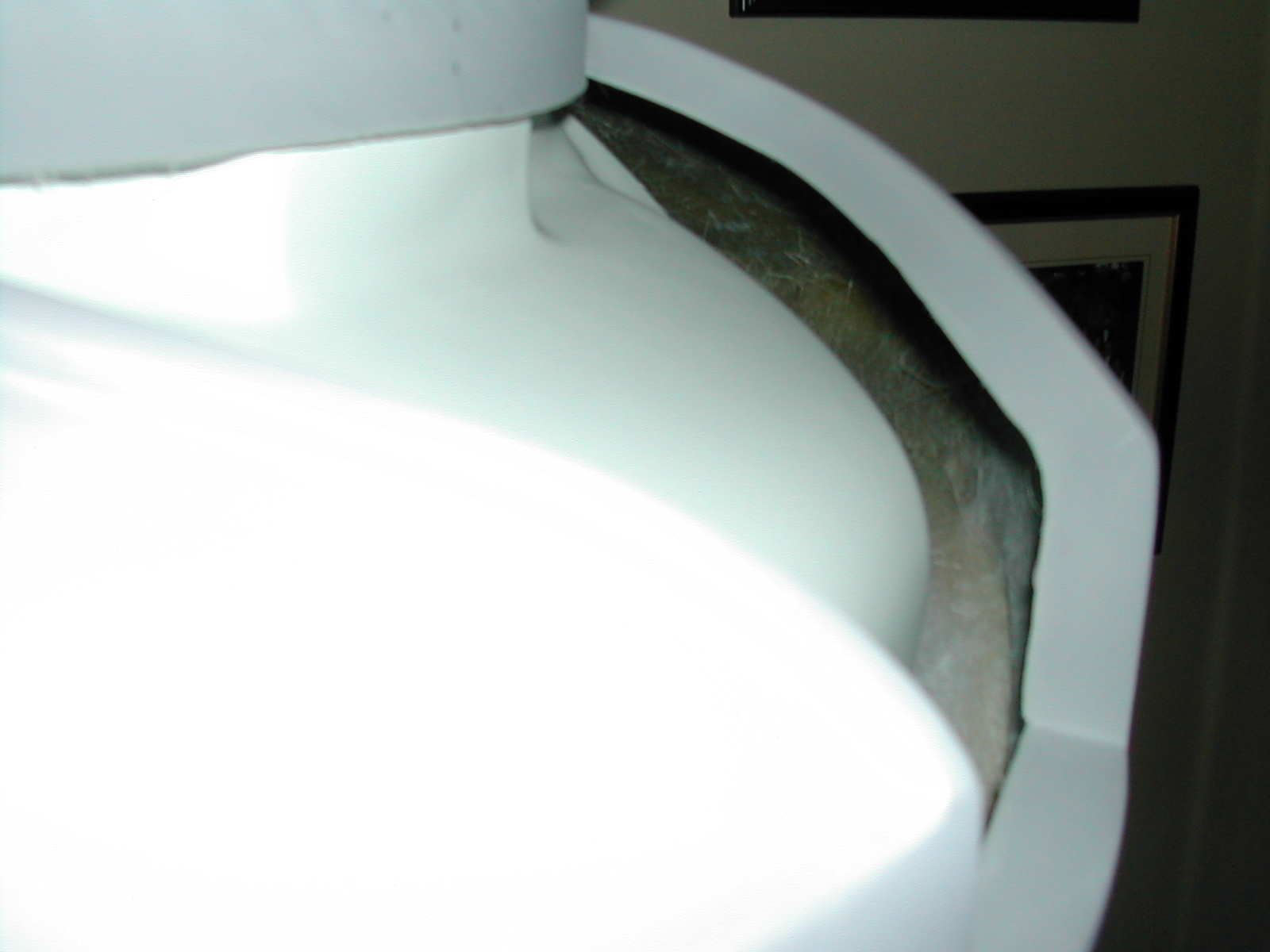

builders have been using does not fit the torso properly. Look at the

unsightly

and unnecessary gaps between the backplate and the torso:

There is no reason for these gaps. They did not exist in the original robot. In fact, the neon tubes were tight up against the torso in the original, as these photos illustrate:

Another thing that I have noticed is that the

bottom most neon tube is just above the lower lip of the robot's

"mouth."

My neon backplate is so constructed that the bottom most neon tube

would

fall below this lip. Clearly, I will have to remake the neon backplate.

9. Fit

the acrylic vents with their aluminum sliding

channels into the torso

The four acrylic vents as well as their aluminum

sliding channels were designed and built by Craig Reinbrecht. One can

well

appreciate the difficulty in building acrylic vents that have exactly

the

right curve so that they match the inner curve of the robot's torso

perfectly.

Building a Lost in Space robot from scratch gives one a lot of

personal

pride of accomplishment, but it is also a great relief knowing that

master

craftsmen have already solved some of the most problematic building

difficulties

and that they are willing to share their expertise and the fruits of

their

labors.

10.

Attach the programming bay

This beautiful piece of workmanship was designed

and built by Craig Reinbrecht. The right side wall of the programming

bay

is smaller then the left wall so that an aluminum channel for the

acrylic

vent can be fitted to it. The larger left wall acts as a break for the

vent, preventing it from sliding to the left.

11. Have

the torso professionally painted by an

auto body shop

I have decided that I will not have the torso,

or any other part of the robot, textured. There is no question but that

the torso and other parts of the original robot costume were textured

before

painting. This served to reduce and eliminate glare from studio lights

reflecting off the robot and bouncing into the motion picture camera

lens.

Texturing also served the very useful purpose of reducing the

visibility

of flaws, repairs, and damage. It is unlikely, though, that a real

robot

would be textured in this same way. Bearing this in mind, my robot will

remain free of texturing. I fully respect those builders who elect to

add

texturing to their robot's torso, but my robot, as I have stated

elsewhere,

is intended to be a realization of the robot from

Lost in Space

as if it had been a real robot rather than a costume and stage

prop

in a television series.

12. Install the electronic components